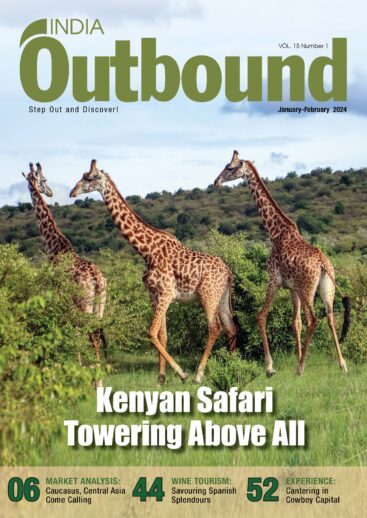

Follow us on a journey into the wilderness in Kenya as we move from the cacophony of Nairobi to Amboseli, alive with sounds much more pleasing to the ear. Roars of distant lions seem to move in rhythm with buffalo grunts and elephant trumpets, while we feed the giraffes and encounter the proud and colourful Maasai tribe.

Africa heals the soul. Though I had heard this often enough, I could not really fathom the meaning until the moment I set foot in Kenya. This feeling of well-being began the instant I landed in Nairobi, the busy capital of Kenya. We were driven straight to our hotel – the Ole Serini, about 30 minutes from the airport. ‘‘It is the only hotel facing the national park,’’ our driver said. ‘‘A national park in the city?’’ was all I could ask in surprise.

Indeed, Nairobi is one of the rare capitals in the world with a national park that is home to about 400 wild animals, including lions, cheetahs, hyenas, buffaloes, leopards, rhinos, giraffes, deers, and zebras. Every morning, I could see some of them from my room, which boasted a direct view on the wide open grass plains, with skyscrapers in the backdrop.

Giraffe centre in Nairobi

The India connect

Next morning, as I took my breakfast on the terrace, I was pleasantly surprised to see that almost 60 pc of the restaurant menu had Indian dishes. The connection between India and Kenya dates back to the 15th century when the first Indian merchants settled in Nairobi and other East African cities. Numerous Indians migrated to the region during the British rule and were employed as guards, police officers, clerks, accountants and indentured labours for the East Africa Protectorate.

Today, Indians are recognised as a ‘tribe’ by the government of Kenya and some of them have mixed with the local population, resulting in very interesting personalities such as Diwan Singh, a renowned tourist guide who specialises in Kilimanjaro trails. ‘‘My father came from Punjab by ship to work as indentured labour to build the Kenya-Uganda Railway. He eventually started working as a clerk for a missionary and that is where he met a beautiful Maasai lady. They got married and I and my nine siblings were born,’’ recounts the 60-year-old man who proudly wears a turban. ‘‘I am a Sikh but I also follow some of the Maasai traditions : we are very close to nature and wildlife,’’ he says, in somewhat halting Punjabi. Of course, nature and wildlife are the main reasons why tourists come to Kenya. National parks and reserves occupy 8 pc of land in this country. Since we had just a day to spend in the capital, we first headed to the Giraffe Centre and the David Sheldrick Elephant Orphanage.

Don’t show me your tongue!

I am usually wary of visiting places that showcase animals —it is painful to see them exploited to attract tourists, sometimes forced to perform ‘entertaining’ acts or exposed to frequent contact with the humans and the camera flashes, without any regard to the impact on their health. But the Giraffe Centre of Nairobi turned out to be a pleasant surprise. You can feed the giraffes, but only if they come voluntarily to you. The animals here have a lot of space and freedom of movement.

Founded in 1979, the Giraffe Centre protects the endangered Rothschild Giraffe and releases all the animals back into natural reserves. Many local kids come to visit because protecting nature and wildlife begins with educating people. ‘‘It’s actually a much better way to teach the kids about animals because here we love them and respect them. It’s not a zoo where animals are imprisoned. So far we have released about 40 giraffes back into the wild,’’ says Jenny, a young Kenyan girl working at the centre.

I tried feeding a giraffe that had wandered to the observation tower where I stood and suddenly I realised that I was as tall as the giraffe in front of me! I first thought the giraffe was an adult, but I was wrong. ‘‘A newborn giraffe is already 6 feet tall and weights 70kg,’’ Jenny told me. Her long tongue softly took the small croquette from my hand. She asked for more and when she got bored, she gave a soft headbutt and ran back to her park.

The centre also organises walks on nature trails that take you through the wild. You can spot the animals and it gives you a totally different perspective of nature.

Not far from the centre is another orphanage, but this one is for baby elephants. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust is a pioneer in the rescue, rehabilitation and release of orphaned baby elephants. The orphanage is quite modern and has been designed like a house for the calves. Tourists can only see them when they are taken to their park, where they play and are fed by their guardians. ‘‘The guardian plays the role of a mother to the elephant, they even sleep with them in order to make them comfortable and loved,’’ explains one of the guides. You can also adopt an elephant and sponsor his rehabilitation. The centre will send you news in the form of photos and videos of the calf you decide to adopt, till he is released back in the wild. So far the centre has managed to save 150 calves.

Train ride to Amboseli

After this unique experience, I could not wait to get into the real wilderness and see the animals in their own environment. One of Kenya’s most popular national parks is Amboseli, crowned by Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest peak, standing tall at 5895 metres above sea level and about 700 metres taller than Mount Kenya, the second highest peak in the continent. Amboseli is home to over 1500 elephants.

To get to Amboseli from Nairobi, you have different transportation options. A car can take you there in about 4 hours and 30 minutes, a small aircraft lands directly in the reserve in about an hour and a new train service takes 75 minutes, during which you get to chat with the locals.

The Nairobi train station looked almost like an airport terminal. Do come early, at least an hour before departure as the way to the coaches is quite long and tedious, with several security points. Once you have passed this, a beautiful hostess welcomes you onboard and the journey eases into a more peaceful pace. We were lucky ; we travelled first class (about KES 790 or INR 575). The coaches are new and well maintained, with large windows and roomy seats, and all the accessories to allow you to work during your journey, recharge your phone or simply read a book. You are offered free tea and coffee and can buy other food and beverages as well. The most interesting part of the journey was definitely the view through the window, from the tall skyscrapers of the city we soon reached large patches of the savannah where we could spot animals such as deer, buffaloes and ostrich.

We got off the train at the Emali station and took a cab to the natural reserve, about an hour and 30 minutes from here. ‘‘Get ready for the African massage,’’ our driver and guide Julius warned us as the vehicle juddered through the rough, potholed road. It wasn’t exactly as comfortable as the train ride.

Spot the elephants

As soon as we entered the national park, giraffes loped over to greet us. A little further, at the gate to the national park, some members of the local Maasai tribe were sitting, waiting for a transportation to go to the city or to sell handicrafts to the tourists. It costs about USD 60 (INR 4500) to enter the park and you can stay at one of the four lodges inside. We stayed at Ol Tukai, a lodge owned by a local Indian. Covering an area of 392 square kilometres, the Park is home to more than 50 other mammal species, including lions and hyenas, zebras, hippos, giraffes, wildebeest and 400 of the 1200 or so species of birds in the entire East Africa.

Once inside the park, almost inevitably, we spotted the elephants first. They mostly live in groups or families, except for a few adult males who live independently. According to members of the Amboseli Elephant Research Project which has its centre inside the National Park, there are about 58 elephant families in the reserve. Since 1972, researchers and scientists have been observing and listing the elephants. ‘‘Our research is an important source of baseline data on elephant social and reproductive patterns and is used as a model for assessing the status of other elephant populations in Africa and even in Asia,’’ explained a volunteer who recognises some elephants by the shape of their ears and has given them names.

Elephants in Africa have long been victims of poaching for their ivory and it was the case in Amboseli too, but the constant presence of scientists in the park for conducting research on the elephants has helped considerably in preventing poaching. Another important deterrent is the presence many Maasai villages in the reserve.

Maasai people singing and dancing to welcome us in their village

Colourful people

At the gate of Amboseli National Park, I saw a tall young man sitting with his friends. The red-and-black check shuka (stole) wrapped around his body contrasted sharply with the beautiful black colour of his skin. Wearing ornaments made of colourful pearls around his neck, hands and feet, Sontika made a striking presence. This was my first encounter with the Maasai.

The Maasai tribals emigrated from South Sudan in the 15th century. You’ll find them settled between Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro in Kenya and Tanzania. There are about 300 Maasai villages inside the park and the community has been living here for generations, sharing the space with lions, elephants and other wild animals. While some Maasai have migrated to Nairobi and other cities in search of better opportunities, many of them continue to follow their pastoral lifestyle, not because they don’t have access to modern life but because they are happy this way, and most importantly, very proud to belong to the community.

A Maasai may be chatting away in good English over his mobile, but would be dressed traditionally and living in kraals, houses made of mud and cow dung. ‘‘We only eat animals from our cattle and drink animal blood and milk for strength,’’ says Sontika, adding, ‘‘We have a profound respect for nature. We use eco-friendly utensils and other objects, all made with natural elements in our house. There is very little use of plastic in our lives.’’

The red and black colour they wear is related to their god. ‘‘We believe in only one God and we call it Enkai. When the God is black, he is benevolent, when he is red, he is vengeful,’’ explains Sontika. ‘‘Our relationship with our cattle is almost sacred, we believe cattle were given to the Maasai community by God himself and we actually measure wealth by the number of cattle and children one has,’’ he adds. With the Christianisation of the country, many Maasai are now Christians and a minority are Muslims too.

Before meeting the Maasai, I had heard about the importance of warriors in their community. When I questioned Sontika, he said that they do perform a ceremony when a young man enters adult life. ‘‘It is called Eunoto, and it symbolises the beginning of his life as warrior. It means that the young man can now start a family, acquire cattle and be a responsible member of the community.’’

Tradition vs modernity

Being a warrior is a source of pride in the Maasai culture. During the ceremony, circumcision is practiced. According to the tradition, in old times, the young man was asked to kill a lion to prove his manhood ‘‘Maasai are not hunters, this used to be practised long before but very less members follow this now. It’s like the women’s circumcision ritual Emorata practiced when a girl turns 14; this is outlawed in Kenya but a few members still practise it,’’ he explains.

In order to make money for their daily needs and to send their kids to school or university, they sell jewellery and other handicrafts and count on donations from the numerous tourists visiting the area.

‘‘The Maasai community from Tanzania to Kenya has faced many tragedies since the turn of the century, including deadly epidemic and severe drought where our animals perished. Also many of the lands were taken away by the British and used to create ranches for settlers. They were never given back,’’ says Sontika. You can go for a guided visit to a village to understand more about how they live. On this visit, you can also buy some Maasai souvenirs. Of course you can negotiate the price or buy as per your budget, after all the money you will spend here is used for the wellbeing of the community.

As I was going through the temporary market created by the community, trying colourful bracelets and necklaces, an old man sitting by the road smiled toothlessly at me and at this very moment it was for sure the best smile in the world for me.

Medol Ilala osina, goes a Maasai proverb translated as ‘teeth do not see poverty’ meaning that people still smile despite problems…